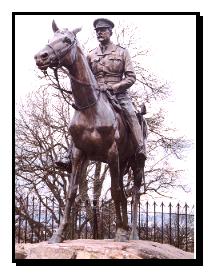

Field-Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, KT, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCIE, ADC (June 19, 1861 – January 29, 1928) was a British soldier and senior commander (Field Marshal) during World War I. He commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) during the Battle of the Somme and the 3rd Battle of Ypres. His tenure as commander of the BEF made Haig one of the most controversial military commanders in British history.

Early life

Haig first saw overseas service in India, in 1887, where he was appointed as the regiment's adjutant in 1888, giving Haig his first administrative experience.

He saw his first active service in Kitchener's Omdurman Campaign in 1898, where he was attached to the cavalry forces of the Egyptian Army, acting as Chief of Staff to brevet Lieutenant-Colonel Robert George Broadwood.

He served in the Boer War in further administrative positions with the cavalry, acting first as the Deputy Assistant Adjutant General in 1899. Haig was employed briefly as Chief Staff Officer to Major-General John French during the Colesburg operations, then as Assistant Adjutant General of the Cavalry Division. He was mentioned in despatches four times. His service in South Africa gained him prominence and the attention of French and Kitchener, both of whom would have important roles in World War I.

In 1901, he became the commanding officer of the 17th Lancers, which he commanded until 1903. He was appointed Aide-de-Camp to King Edward VII in 1902, remaining in this position until 1904. After leaving the 17th Lancers, Haig returned to India after Lord Kitchener was appointed Commander-in-Chief, India, and became Inspector-General of Cavalry. Having been a captain until the age of thirty-eight, five years later in 1904 he became the youngest major-general in the British Army at that time.

The following year, Haig married Dorothy Maud Vivian; they would have four children - Alexandra (born 1907), Victoria (born 1908), George (born 1918), and Irene (born 1919).

Haig returned to England in 1906 as the Director of Military Training on the General Staff at the War Office]. During this time, Haig assisted Secretary of State for War Richard Haldane in his reforms of the British Army, which was intended to prepare the army for a future European war. He took up the post of Director of Staff Duties in the War Office in 1907. A second return to India came in 1909, when he was appointed as Chief of the Indian General Staff. He was appointed GOC Aldershot from 1912 to 1914 and Aide-de-Camp to King George V in 1914.

In the Army Manoeuvres of 1912 he was decisively beaten by Sir James Grierson despite having the odds in his favour.

Career

Upon the outbreak of war in August 1914, Haig helped organise the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), commanded by Field-Marshal John French. As planned, Haig's Aldershot command was formed into I Corps, giving him command of half of the BEF.

Tensions quickly arose between Haig and French. Haig and Lord Kitchener, who was now Secretary of State for War, clashed with French over the positioning of the BEF. French argued to the war council that it should be positioned in Belgium, where he had confidence in the country's many fortresses, while Haig and Kitchener proposed that the BEF would be better positioned to counter-attack in Amiens, stating that the BEF would have to abandon its positions in Belgium once the poorly-equipped Belgian Army collapsed, forcing the BEF into retreat with the loss of much of its supplies. During a royal inspection of Aldershot, Haig told King George V that he had "grave doubts" about French military competence.

The BEF landed in France on 14 August and advanced into Belgium, where John French intended to meet General Lanrezac's French Fifth Army at Charleroi. During the advance the BEF experienced their first encounter with the Germans at Mons on 23 August. The Germans were bloodied in the battle but the BEF began a withdrawal after Lanzerac ordered his army into retreat exposing the BEF's right flank.

The retreats of I and II Corps had to be conducted separately because of the Forest of Mormal. Both corps were supposed to meet at Le Cateau but I Corps under Haig got no further than Landrecies, leaving a large gap between the two corps. Haig's reactions to his corps' skirmish with German forces at Landrecies led to him sending an exaggerated report to John French, causing French to panic. The following day 26 August, Horace Smith-Dorrien's II Corps had to make a stand at Le Cateau unsupported by Haig. This battle further delayed Germany's advance. The French commander Joseph Joffre had ordered his forces to retreat to the Marne on 25 August, compelling the BEF to undertake a lengthy and arduous withdrawal to conform to the French movements. John French's faltering belief in the competence of his Allies caused further indecision and led to him deciding to pull the BEF out of the war by withdrawing south of the Seine. Lord Kitchener intervened on 1 September, making a visit to dissuade French and order him to continue cooperation with Joffre's forces. The stand to defend Paris began on 5 September, in the Battle of the Marne. The BEF weren't able to participate in the battle until 9 September. The battle ended the following day; the German advance was defeated, prompting them to initiate a withdrawal to the Aisne that signified the abandonment of the Schlieffen Plan.

Following defensive successes at Battle of Mons and Ypres (1st Battle of Ypres), Haig was promoted to full General and in December 1914 the I Corps was transformed into the British First Army of which Haig received command.

In December 1915, Haig replaced French as Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, with French returning to Britain. Haig had been intriguing for the removal of French as commander of the BEF and had told King George V that French was "a source of great weakness to the army and no one had confidence in him any more". He directed several British campaigns, including the British offensive at the Somme, in which the forces under his command sustained over 300,000 casualties taking little ground but inflicting casualties on the German army it could not afford and the campaign at Passchendaele (3rd Battle of Ypres). Haig's tactics in these battles are still considered controversial by many, including the then Prime Minister Lloyd George, arguing that he incurred unnecessarily large casualties for little tactical gain. (When he asked the Canadian Corps commander Arthur Currie to capture Passchendaele Ridge during the final month of the battle, Currie flatly replied "It's suicidal. I will not waste 16,000 good soldiers on such a hopeless objective".

Haig had frequent disagreements and strained relations with both his Prime Minister and his French counterparts, particularly Robert Nivelle and Ferdinand Foch. He also had a rivalry of sorts with General Edmund Allenby dating back to their service in the Boer War, and was instrumental in having him transferred to the Middle East.

World War I

After the war, Haig was created 1st Earl Haig (with a subsidiary viscountcy and a subsidiary barony) and received the thanks of both Houses of Parliament and a grant of £100,000 (1919).

From July 1919 to January 1921, he was Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces in Great Britain

He devoted the rest of his life to the welfare of ex-servicemen, travelling throughout the British Empire to promote their interests. He was instrumental in setting up the Haig Fund for the financial assistance of ex-servicemen and the Haig Homes charity to ensure they were properly housed; both continue to provide help many years after they were created. He was involved in the creation of the Royal British Legion, which he was president of until his death and was chairman of the United Services Fund from 1921 until his death.

He maintained ties with the British Army after his retirement; he was honorary colonel of the 17th/21st Lancers (having been honorary colonel of the 17th Lancers from 1912), Royal Horse Guards, The London Scottish and the King's Own Scottish Borderers. He was also Lord Rector and, eventually, Lord Chancellor of the University of St Andrews.

Later life

Later lifeLieutenant (February 1885)

Captain (1891)

Major (1899)

Lieutenant-Colonel (1901)

Colonel (1903)

Major-General (1904)

Lieutenant-General (1910)

General (November 1914)

Field-Marshal (1 January 1917) Haig's funeral

After the war Haig was often criticised for issuing orders which led to excessive casualties of British troops under his command, particularly on the Western Front, earning him the nickname "Butcher of the Somme". Haig's critics include many younger officers who served in the First World War, making the criticism that they "fail[ed] to understand" the actual combat conditions of the war ring hollow - Haig himself never actually visited the main front though in his dispatches he described the appalling conditions of the Somme accurately..

Along with John Terraine and Gary Sheffield, historians such as Richard Holmes, and Gordon Corrigan are sympathetic towards Haig, Gordon Corrigan in particular arguing that if Haig had really been the blinkered uncaring incompetent of popular legend then he would not have delivered victory. They point out that he faced enormous problems, notably the inexperienced New Armies, the lack of effective battlefield communication (radios then being too large for the battlefield but telephone wires impossible to lay under artillery barrage, so that senior generals had little choice but to command from chateaux miles behind the front lines), the lack of a decisive arm, the application of new technology and political interference.

Historians favourable to Haig also argue, as did British generals such as Sir William Robertson and Haig at the time, that the Western Front (where a defeat for either side would have exposed either Paris or the Ruhr to occupation) was the decisive theatre of war, where the Germans deployed roughly two-thirds of their army - between 150 and 200 divisions - in well-developed positions, and argue that Lloyd George's schemes to engage the Germans on other fronts such as Palestine and Italy did little to bring Germany nearer defeat. Additionally, in the second half of the war the forces under Haig's command took over the main burden of the Allied offensive on the Western Front.

Modern historians also make the point that mass warfare between Western Armies in World War I (and indeed World War II, in which the most serious land fighting was done by the Soviets rather than the Western Allies) invariably led to huge casualties and that if there was an easy, cheap way to break the trench stalemate, no-one else found it on either side. The only occasion during WWII when Britain took a leading role in breaking the Axis armies in a major area of operations was the breakout from Normandy. On a unit-for-unit basis casualty rates were proportionately higher than the battles of World War One.

Controversy

Haig's tactics were a running joke on the 1989 BBC comedy series Blackadder Goes Forth, where Stephen Fry's role as General Sir Anthony Cecil Hogmanay Melchett, nicknamed 'Insanity' Melchett, with his vast moustache and callous disregard for the lives of his men is a popular caricature of British leadership, with elements of Haig and Lord Kitchener, although his personality is most like that of Sir Edmund 'The Bull' Allenby, without the latter's ability. Field Marshal Haig, played by Geoffrey Palmer, makes an appearance in the final episode, shown setting up toy soldiers on a battle map and then pushing them over, before sweeping them up with a dustpan and brush and throwing them in the bin. In the series, he is portrayed as a complete idiot. His battle plans include 'climbing out of the trench and walking very slowly towards the enemy'. Despite using this plan, Haig cannot understand why the men always seem depressed.

Haig was also played by Sir John Mills in Richard Attenborough's 1969 film, Oh! What a Lovely War, in which he is portrayed as being indifferent to the fate of the troops under his command, his goal being to wear the Germans down even at the cost of enormous losses and to prevail since the Allies will have the last 10,000 men left.

In Anthony Powell's novel A Buyer's Market (book 2 in A Dance to the Music of Time), the narrator attends a dinner party where a controversy over a proposed statue to Haig is discussed, in which one character suggests that the sculptor should show him in a car rather than on a horse.

Other

Lefthit

Lefthit

No comments:

Post a Comment